The Axe

THE AXE: A BOOK

I’m currently working on a book-length object history of the axe for W.W. Norton, part investigation of its symbolism in America’s westward expansion, part interrogation of contemporary tropes of masculinity and wilderness.

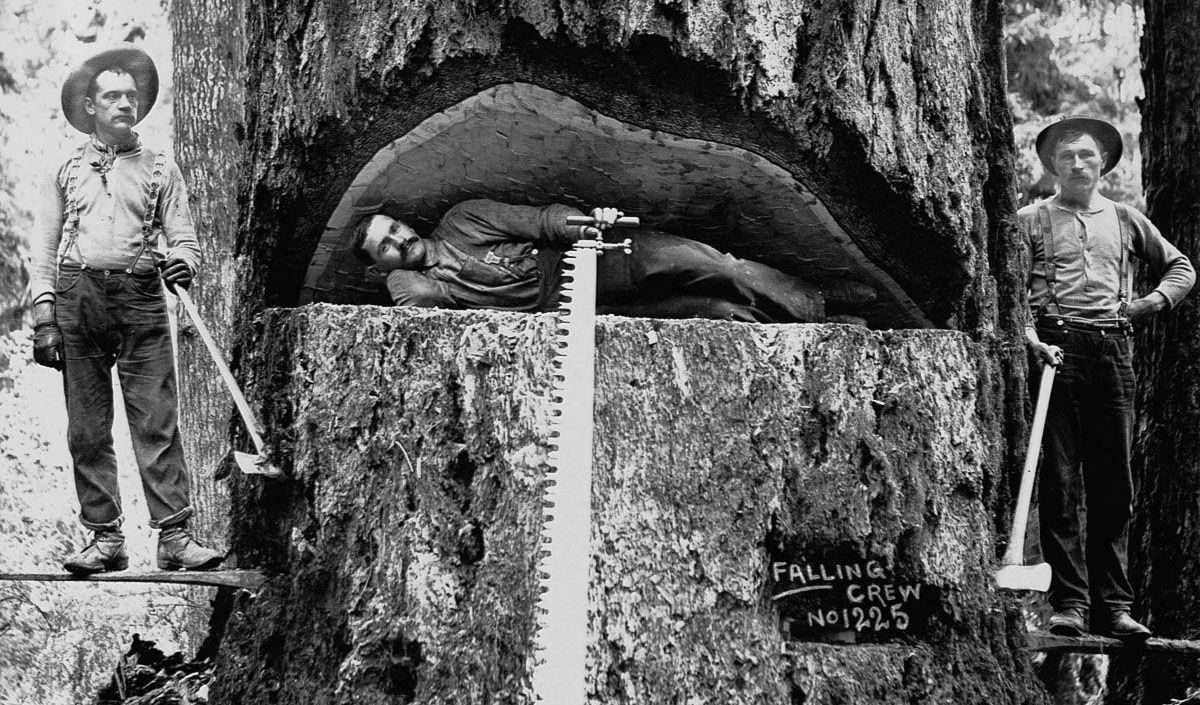

As the American wild recedes at ever-increasing speed, in parallel to our own steady disconnection from the natural world, there has grown a deep nostalgia for the idea of the land, a yearning for that hand-built home on the range. With the rise of a how-to cottage industry that repackages bygone tropes of frontier masculinity for urban creatives, rugged self-sufficiency has evolved into an aspirational lifestyle, manifest everywhere from lumberjack aesthetics to butchery workshops to axe-throwing clubs.

If this nostalgia — this yearning for simplicity and action — has a symbol, it is the axe.

In its 10,000-year history the axe has meant much to human civilization, as tool, weapon, currency, and religious icon. As a physical extension of our endless laboring for fuel and shelter, the axe kept a hundred generations of humankind tethered to the pace and scale of the arboreal world, as we evolved virtues like patience and discipline. As a simple but deeply efficient tool, the axe forced us to consider not just the trees at hand, but the livelihood of the forests that would remain over generations.

But it’s not that simple.

In the second half of the 19th century, as America grew ever westward, so too did its mythologies of freedom, independence and adventure, glorified campfire stories told to lure axe-wielding footsoldiers into capitalism’s endless war of extraction.

How do we balance these romantic fantasies of the rugged woodland life — based as they are in dominion and patriarchy — with appropriate respect for the labor that connects us meaningfully to the natural world at a sustainable scale? How can we strip our reverence for wilderness of its privileged codes, its self-serving blindness to race and class in America? How do we apply the hard-won lessons of frontier competence to the contemporary Anthropocene without taking a step back into the past?

Along with a picaresque survey of the odd, beautiful, and sometimes grim significance of the axe to human history, both material and cultural, I’ll try to answer some of the questions above . . .